MY EXPERIENCE WITH SOME CHARLATANS HIJACKING RATIONAL THINKING

Throughout architecture academia in India, students are asked to design keeping in mind the context of the site, the landscape, the cultural aspects of the region, the bye-laws, and so on. Once the student graduates and starts working, they realize all that was total garbage in a real sense within the Indian context. The typical Indian client has been so brainwashed by superstition and pseudo-religious preaching that they have lost the ability to question the irrational and to try and defy obvious superstition.

I will not argue the merits of an architect when compared to a vastu “consultant” (an epithet I strongly dislike to associate with such frauds), as it demeans the value added to a project by a skilled, and trained member of the former group. The blatant fear-mongering of a practitioner of this pseudoscience has been causing permanent damage (in some cases quantifiable damage) to the built environment in the city. Architects are having to compromise on almost every single aspect of designing a building due to the deep-seated fear of the unknown which has been actively propagated by the charlatans in our midst.

From a scientific point of view, Indian buildings today would be classified as being quite inefficient when judged in terms of natural lighting, ventilation, or even general planning. But from an Indian point of view, the same building might be perfect, as judged from the “Vastu compliance” standpoint. If a site or a building is not vastu compliant, the property value immediately drops by a certain percentage, and some ‘poojas’, and vastu ‘correction’ interventions are made to the project to counter the “evil forces” that might be lurking within the yet unoccupied building of brick and concrete. One might argue that this lends a unique “Indianness” to the designs. But, is that something we would like to be representative of Indian architecture? Inefficiency, and wastefulness?

This makes me ask – what does vastu contribute to a project? Apart from the artificial peace of mind given to the client, I can think of nothing else that can’t be achieved in a better form from a scientific approach to the design process. Vastu has led to the homogenization of modern Indian architecture to an ideology away from “Form follows function”, or even “Function follows form”, to a very disappointing “Form and function follow vastu”. The fear-mongering by the charlatans in our midst has led to the impractical, and often heavy underutilization of land. This belief in vastu gets further reinforced when we have Chief Ministers such as K. Chandrashekar Rao demolition existing secretariat buildings to build a new “Vastu compliant” secretariat during the pandemic. The very people who are meant to represent the best in us succumb to the appeal of this false balm called vastu.

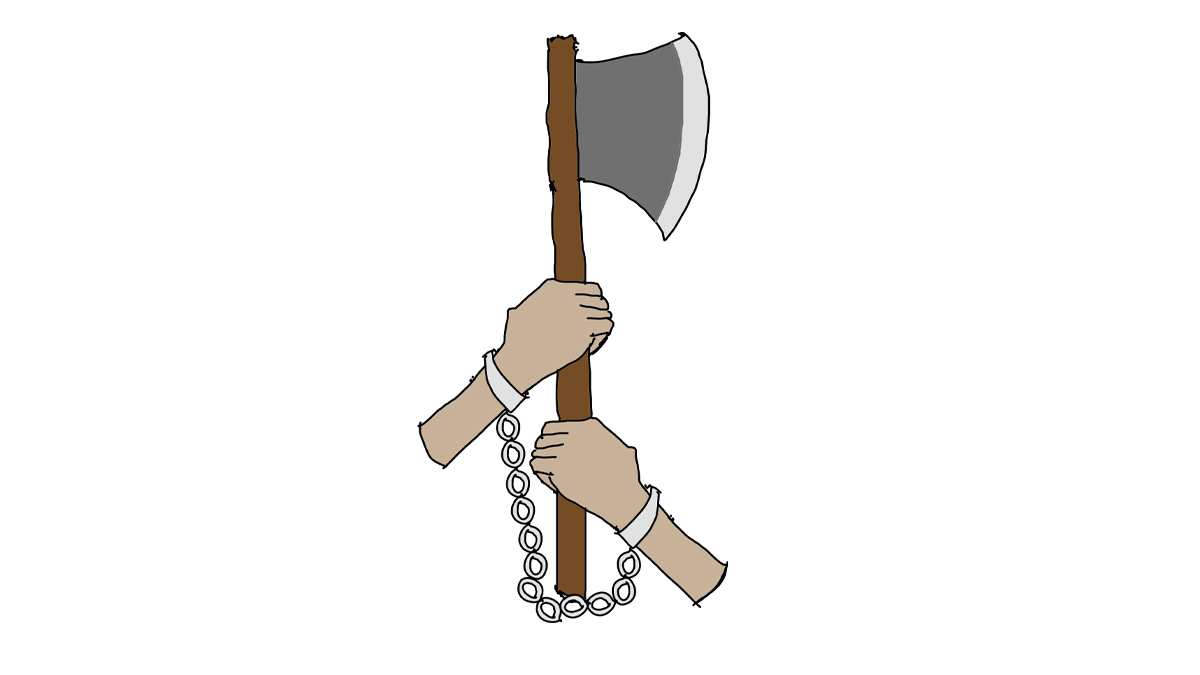

At a personal level, with my few years out of architecture school, I have witnessed first-hand the heavy deterioration in the measurable quality of life in a building brought by vastu. The architectural gymnastics that have to be performed to counter potential ill will from an inanimate structure are astounding. Burying a copper wire to “straighten” a site, having a deeper sump tank to ensure one quadrant is deeper than the other, foregoing cross ventilation, and even avoiding a rainwater harvesting tank because it would make the housing project incompatible with vastu are some of the insane directives that have been forced upon the clients – and by extension, the architects too. All sorts of unnecessary and unscientific compromises have to be made to appease the baseless fears evoked in the clients by these bottom feeders. These fraudsters have captured the imagination of the people using fear and religion, upending the years of logical thought that a person gains through real-life experience. If one of these vastu peddlers truly believes in the nonsense that they spout from their mouths, they should be subjected to psychological evaluation. And even if they don’t believe in it, they should still be subject to the evaluation – we might end up learning something about manipulative disorders.

“If someone doesn’t value evidence, what evidence are you going to provide to prove that they should value it? If someone doesn’t value logic, what logical argument could you provide to show the importance of logic?”

― Sam Harris