CRIME, GUILT, AND PUNISHMENT – A REVIEW OF THE CLASSIC NOVEL BY FYODOR DOSTEYEVSKY

THE BOOK

What is the value of a human life? Are some lives more valuable than others? Do some people have a natural right to take the life of others? These are few questions that man has been asking himself since he developed a moral compass, and these are the questions that Fyodor Dostoyevsky deals with in Crime and Punishment.

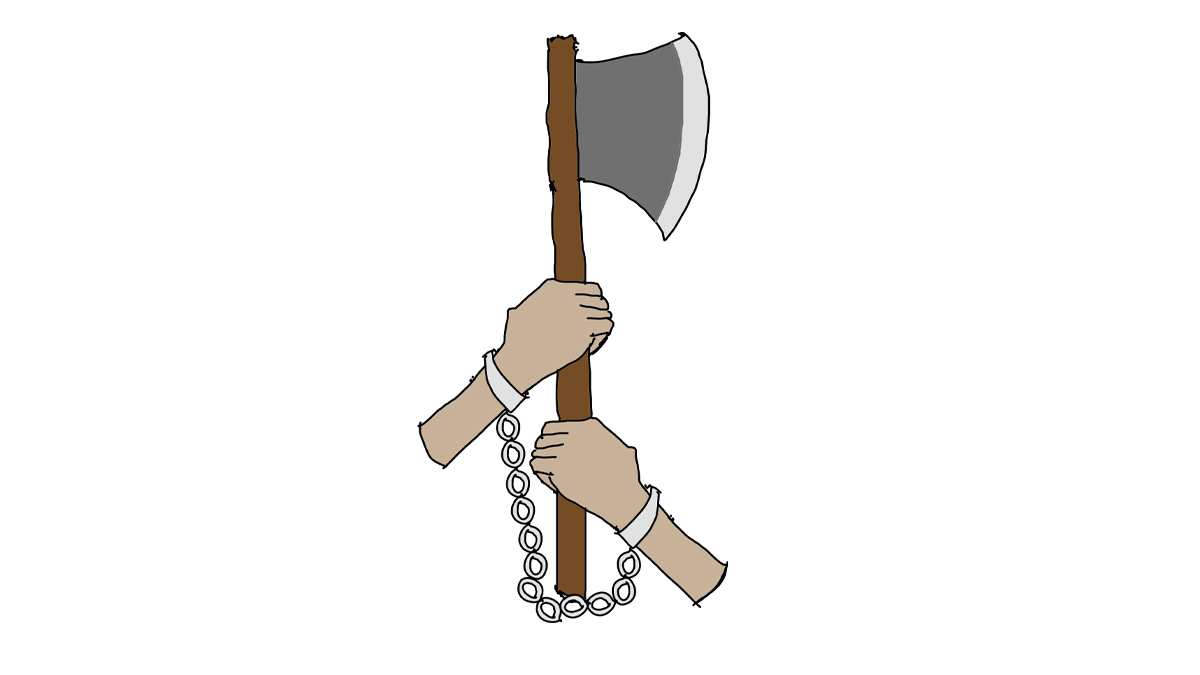

Crime and Punishment is a lengthy treatise in the form of a novel on the psychology and morality of a crime. It has examined the mind of one individual who commits one of the gravest legal crimes – murder. The story is set in St. Petersburg of the late 1880s and is about the murder of an old pawnbroker and her sister by the antihero, Raskolnikov. We find the lead character Raskolnikov as a conflicted individual with a theory on “the right to kill”, and ends up putting the theory to practice. The theory is simple. People are of two categories – the leaders and the followers. The leaders are those who take humanity forward and have the moral authority to take lives as they see fit. Raskolnikov holds Napoleon as an example of this man. The other category is what the majority of people fall under, and are for whom the rules and laws are written for.

The more we learn about Raskolnikov, the more we learn about Dostoyevsky too. A man who was quite ahead of his time with ideas such as equality for women, open marriages, the politics of an unequal society, class discrimination, and the treatment of prostitutes in society. He brings these ideas through very well composed characters who are depicted as intelligent outsiders in society.

Considered to be the first great psychological novel, Crime and Punishment introduces a number of characters in different societal and mental states. The interactions between these characters might seem odd today, but probably was how it the societal construct was in 19th century Russia.

The constant sense of panic and guilt in the book made me quite uncomfortable, but I assume that was the intended reaction. The scenes between Raskolnikov, and the investigator Porfiry are the best parts of the book and here we see a detachment in the question of murder itself. The question of “Is murder correct?” shifts from morality to legality. The questions tormenting Raskolnikov about the murder were purely concerned with whether he has a moral right while Porfiry is unconcerned with it and only follows the letter of the law.

Crime and Punishment is an interesting book that could do with quite a bit of editing today. The first two books can be heavily edited and compressed into a single part. The translation itself can undergo another translation into something more modern.

[I read the Constance Garnett translation (and would recommend this over McDuff. I read the Pevear/ Volokhonsky of ‘Notes from the underground’ and did not find it very appealing) and I believe the translation can be further translated to an even more modern English.]

Note:

The major side characters of the novel include Raskolnikov, his friend Razumikhin; his sister Dounia and their mother; Peter Petrovich, a rich manipulative suitor for his sister; Porfiry, the officer in charge of investigating the murders; the proverbial prostitute with a golden heart – Sonia, the daughter of Marmedalov – a drunk he met in a bar; Nikolai – a young painter working below the apartment where the murders occur, and who confesses to being the murderer, and Svidrigalov, a man in whose house Dounia worked as a governess.

THE STORY AND THEMES

The antihero, Raskolnikov, is an intelligent young man who has been subjected to penury and forced to quit law school as he is unable to pay the fee. After great thought, he decides to take the life of a rude old moneylender and steal from her. He initially justifies this in his mind several ways, calling her an evil hoarder that the world will be better off without; and at the end even resorting to omens. But on the day he kills the woman, he enters into a frenzy and when her sister stumbles upon the crime, he kills her too. These murders turn out to be more than what Raskolnikov could take, and he falls into a psychosomatic illness. Raskolnikov runs from the scene, buries his loot, and gets home and immediately falls sick. Raskolnikov’s is taken care of by his servant, Anastasia and his friend Razumikhin in this time. When he awakens, he spurns everybody around him and reacts only when they talk about the murdered pawnbroker.

Razumikhin and Raskolnikov go to meet Porfiry, the official investigating the murders. The confrontations between Porfiry, an intelligent investigator, and a troubled Raskolnikov form the most intense parts of the book. Porfiry immediately hints at his suspicion on Raskolnikov and appears to show all his cards while interrogating Raskolnikov. He pounds Raskolnikov over and over, goading him into letting something slip. The first time, Porfiry and Raskolnikov meet at Porfiry’s house when Raskolnikov is taken there by Razumikhin. In this instance, Porfiry shows that he is one step ahead of Raskolnikov when he questions Raskolnikov on an article he had written for a magazine anonymously. Thus ensues an intense “cat & mouse” psychological battle between Porfiry and Raskolnikov where Porfiry shows his superior understanding of the criminal mind, taking advantage of every weakness displayed by an agitated Raskolnikov. His observation torments Raskolnikov endlessly and he barely escapes him. After intense arguments with Porfiry, where he is indirectly, and later directly accused of being the murderer, Raskolnikov becomes increasingly desperate and cuts off contact with his family and entrusts their wellbeing to Razumikhin.

He tries to find redemption in Sonia, the woman who is the antithesis of everything Raskolnikov; the woman who sacrificed her body, soul and integrity so that she can provide for her family. A woman who takes insult and pain so that her step siblings and delusional step mother don’t have to. As Razumikhin spirals into further desperation and instability, he tries to find purpose and meaning. He concludes that he is not one among the few “leaders”, but is still conflicted on whether he feelsguilt on the act of murder itself.

CRIME, GUILT AND PUNISHMENT

If I could add one word to the title, it would be “guilt”. As the name suggests, the book plays with the themes of crime and punishment. But along with them, the concept that runs throughout the book is guilt. Marmedalov’s guilt for ruining his family with drink, resulting in Sonia becoming a prostitute; Sonia’s guilt for ruining the reputation of her family with her work, her mother’s guilt in being unable to take care of her family, Svidrigalov’s guilt for his approaches on Dounia, Razumikhin’s guilt in his inability to save Raskolnikov, Raskolnikov’s guilt for the murders, and even Nikolai’s religious guilt in “not suffering”. This undercurrent of guilt felt through every page makes us quite uneasy.

Dostoyevsky takes us into the minds of various characters from various walks of life, exploring the guilt manifesting in people in various ways – from illness to suicide. This depth of understanding of the human psyche ensures that Dostoyevsky will remain relevant for ages. We might all relate to the motives and guilt of at least one character and find the psyche of another to be completely absurd. It is the guilt that leads to the conclusion of the story and I found myself quite conflicted with the ending. Putting myself in that place, would I have done the same thing? Probably, but probably not. We might never know unless we find ourselves in that place.